International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 365

ISSN 2229-5518

Resurrection and being of a Haat: case study of rural markets of the eastern plateau region

Aditi Sarkar, Pabitra Banik, Rana Dattagupta

Abstract— Haats/bazaars since ages have been essential place for exchange of commodities where farmers and local people have congregated to conduct trade since times immemorial, exchange ideas, engage in social, cultural, religious as well as political activities. They are not only commercial venues but have been significant hubs of festivity and cultural exchanges.

There have been ample reasons for the existence of the haats/bazaars, so have been the complexities that have plagued their exist- ence and been instrumental in their extinction. In order to identify the particular responses of haats/bazaars to precise fluctuations in the parameters that determine their well-being, an extensive study was conducted through painstaking fieldwork using structured questionnaires. Based on the information, the reasons for the revival or generation of a new haat/bazaar were analyzed. Such analyti- cal study based on complete quantitative and qualitative primary data obtained directly from the haats/bazaars has been almost zilch for W est Bengal (India).

Index Terms rural agricultural markets, Purulia, periodic markets, Haat/Bazaar, extinction, revival.

—————————— ——————————

1 INTRODUCTION

Rural market refers to a market or market place, either

permanent or temporary in nature, mainly along the street. They have long been an essential place for exchange where farmers and local people have congregated to conduct trade since times immemorial. They play a pivotal role as a scene to gather news and information, to exchange views and knowledge, to engage in various social, cultural, religious, and even political activities. They are venues for both commerce as well as festivity and exude a feeling of unity and strength. These occasional gatherings lead to traffic in social, cultural, and economic exchanges. Transactions of agricultural goods take place in regulated markets, wholesale markets and rural periodic markets. The rural weekly markets exist as India's grassroots retail network known mostly by their local names –

‘Haats’ (West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa), Santhe (Karna- taka), Sandhai (Tamil Nadu). The term ‘bazaar’ has a Persian origin that gained momentum in India [5]. They are the oldest marketing channel and constitute an important segment of rural and overall economy. Haats/bazaars occupy the lowest rung of the marketing system in rural Bengal [3]. The haats are often mobile and flexible as they shift from one location on one day to another on the next day and the locations vary in nature too. They can very well be marked as a place for politi- cal, economic, social, and cultural transactions. Periodicity is

————————————————

• Aditi Sarkar is currently pursuing PhD in Engineering in Jadavpur Uni- versity, India, PH- 9830621995. E-mail:aditi.iirs@gmail.com

• Pabitra Banik is currently Associate Professor at Indian Statistical Insti- tute, Kolkata, India. E-mail: banikpabitra @mail.com

• Rana Dattagupta is currently Professor Emeritus at Jadavpur University,

Kolkata, India. E-mail: rdattagupta@cse.jdvu.ac.in

one of their defining characteristics, which encourages the local inhabitants to congregate only on the specified days set aside for transactions. Based on this uniqueness, the rural markets of West Bengal are categorized into ‘Haats’ (the peri- odic markets) and the ‘Bazaars’ (the daily markets). Haats are held weekly, scheduled on the day the employees get their

'hafta', as the payments to villagers still are made on a weekly basis. They seem sufficient to meet the local demands since the necessities of the peasants in a subsistence economy have al- ways been limited. Moreover, since poor transportation and communication facilities often serve limited areas, markets of the same locality always meet on different days of the week. As a result, the villagers could use manifold markets. This access to several rural markets also expedites the peasants to deal their surplus agricultural products as well as artisanal goods. These exchanges involve several hands, resulting in the involvement of various traders at various levels of the market hierarchy. Reasons commensurate for the existence of the rural markets are ample. However, the rural agricultural markets are often plagued by complexities, mostly to deal with lack of information, control of intermediaries, forced sale, infrastruc- tural breaches, lack of proper transportation and communica- tion to serve greater areas and highly fragmented and unor- ganized agricultural markets. World Bank (2008) remarked how the shabby road conditions coupled with the undevel- oped infrastructure limit the farmers' as well as the buyers' access to rural markets. As long as they are affected by such complexities, the haats/bazaars can seldom contribute to the development of the rural sector [1]. Studies in Bangladesh have depicted how lack of development arises as a conse- quence to infrastructural deficiencies [2].

In West Bengal, the marketing of agricultural commodities has been promoted through a network of Regulated Markets. There are about 44 Regulated Market Committees (RMC), 2925

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 366

ISSN 2229-5518

periodic haats and 279 wholesale markets in West Bengal. The establishment of these regulated markets throughout the state has helped in creating orderly and transparent marketing conditions in primary assembling markets. However, the rural periodic and local markets in general and the tribal markets in particular, have been left out of its ambit even though these haats are extremely pro-active in the context of rural agricul- tural economy. The sole aim of this study was to address to this ennui towards the haats/bazaars and highlight their dy- namic responses to such indifferences.

Objective:

Considerable work has already been done in India and abroad on market research and marketing chain of agricultural pro- duces. However, the study on the health of the rural periodic markets, their eventual decay, and astounding resuscitation has been rare and virtually zilch in West Bengal. With the pre- viously mentioned backdrop, the principal objective was to highlight the natural mechanism of the rural haats/bazaars to revive and regain its full vigor even after an inevitable extinc- tion. The dynamics of the rural periodic markets is not always very critical or complicated. In this paper, an attempt has been made to study this particular dynamics of extinction and re- vival of the rural periodic markets through a detailed quanti- tative as well as qualitative analysis.

2 AREA OF OBSERVATION

The study resulted from an extensive tour of the Jhalda I block in the Purulia district of West Bengal, India. The area belongs to the eastern plateau region of India. The tour involved a gap of approximately three years. Each haat/bazaar of the block was intensively scrutinized not only on the operational day but also during the operation. The choice of Jhalda I block as the study locus was due to its unique location. It is the western most block of the western most district (Purulia) of West Ben- gal sharing a common boundary with the neighboring state of Jharkhand. The area in terms of its rural periodic markets has gone through some significant phases and has unique charac- teristics to them. Even though from agricultural point of view, the block does not have much diversity due to its extremely rugged nature, the rural agricultural marketing yet has a col- orful and significant flavor.

3 DATA AND SOFTWARE

The study envisaged the use of geo-spatial information in terms of the geographical location of each haat/bazaar as well as additional information associated with each location. This meant the use of Garmin GPSMAP 76CSx to capture the haat/bazaar location and ArcMap 10 to spatially plot them for easy viewing. For the attribute information generation, a con- siderable amount of data from both primary as well as sec- ondary sources was obtained.

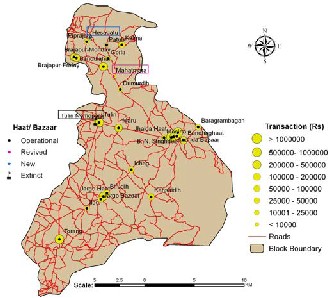

Figure 2.1: Location Map of the study area

3.1 Primary data:

A tedious amount of primary data was collected directly from the haat/bazaar using Market Information schedule.

3.2 Ancillary data:

Ancillary data were required for the geo-spatial database crea- tion required for the study. A detailed tabulation has been provided below (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Ancillary data used for the study.

1. SOI Topographical map sheets of Purulia district – at scale

1:250,000 (Nos. 73 E; 73I; 73J);

2. National Atlas and Thematic Mapping Organization (NAT- MO) District Planning map (DPM) series at 1:250,000;

3.3 Software used:

• ArcMap 10;

• Garmin GPSMAP 76CSx, MapSource@ Trip and Way- point Manager;

• Microsoft Office.

4 METHODOLOGY

The study was conducted over the rural markets of Jhalda I block of Purulia district incorporating a well-drafted method- ology. Once the area was finalized, prior to the field visit, in- formation about the existing haats/bazaars was extracted with the help of local field resources. Accompanied with this detail the block was visited and firsthand information about more haats/bazaars were obtained. The field survey was conducted at two phases during 2009 and 2014. The exact geographical loca- tions were identified using the Global Positioning System and each market was identified in their true nature with all neces- sary attribute information. A detailed survey of the haats/bazaars of the block was accomplished following which

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 367

ISSN 2229-5518

the data collected was treated and used in generating an in- formation system.

The first phase marked the initiation of the survey of the rural periodic markets at a detailed level and at the second phase, the survey was purely to verify the previously collected in- formation along with extraction of supplementary infor- mation. An exhaustive market survey questionnaire was pre- pared before the actual survey of the periodic markets began. The interviews were conducted based on this set of a well- sketched questionnaire. During the operational hours, the haats/bazaars were visited; the users (consumers and vendors, haat owners) were interviewed in depth based on the struc- tured questionnaire. The basic data related to the haats/bazaars along with their respective geographical coordinates were cap- tured.

Since the existing land administration system is still a continuation of the British legacy, the block has been consid- ered as an administrative boundary. Hence, the analysis was pre-conceived with the block boundary as the basic theme boundary. Based on the secondary map sources, the base map creation was accomplished to obtain the block level digital database. It involved procurement of topographical map sheets from Survey of India, converting them to digital format and then associating them with real physical space by the pro- cess of geo-referencing. Subsequently the district boundary feature-class was vectorized and eventually the individual block was extracted (clipped) out of it. The topographical map sheets along with the district planning map and Google Earth were used to create digital road network coverage. The loca- tions (Geographical latitude and longitude) of the haats/bazaars were captured using GPS tracker. MapSource waypoint man- ager was used to transfer the GPS waypoints (geographic loca- tions of the rural markets) from the Garmin device to the computer and had then been spatially mapped using GIS plat- form ArcMap 10. Once the mapping was completed, the peri- odic markets were furnished with all the attribute information collected from the field survey.

Once the entire geo-database was prepared, an extensive analysis was executed to study the dynamic response of the rural economic centres in relation to their characteristics. Based on the information assembled, the reason behind the existence, development, or extinction of the particular haat/bazaar was studied purely on a quantitative basis.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

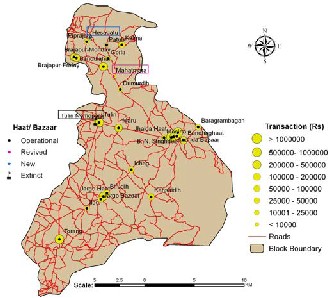

The haats/bazaars were observed to be scattered and not very close situated to each other. They only appeared along settlements. Since Jhalda I block is not very thickly populated, its rural periodic markets too reflected a similar trend. In the block total twenty-seven haats/bazaars were surveyed including the operational, revived, new and extinct haats/bazaars. It was observed that twenty-five of them were functional of which one had revived just about a year and half ago after a prolonged period of 30 years' dormancy. The

revived Mahatamara Haat (Figure 5.1) used to be a significant large-scale haat about thirty years back. However, due to reasons of extremely poor connectivity and thereby decreasing communication over the time, the market did not survive. It was a major crowd puller of the Jharkhand population, which eventually declined due to obvious reasons of communication problems. Moreover, the serious lack of infrastructural amenities too added up to the causes of dormancy. The Hesahatu Haat began its operation just about two years back. The nearest Piparajara Haat being about 2 km far and with limited transportation facilities, this new location was preferred to be set up on a Sunday by the local villagers for their daily needs. It was mainly because all the nearby haats operate on days other than Sunday and they are visited by the local people. But Sunday being a market-free day, this haat gained momentum. The Tulin Namopara Haat became extinct due to the impact of a nearby Tulin Haat.

Figure 5.1: Haats/Bazaars of Jhalda I block of Purulia

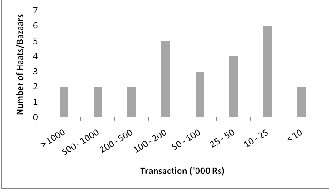

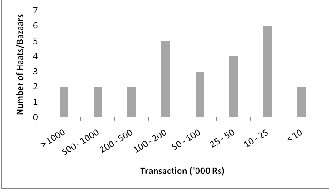

The transaction amount of any haat/bazaar has been considered to be the most vital parameter to judge its health. Based on the transaction amount generated in the currently operational twenty six haats/bazaars of the Jhalda I block, they have been categorized (Figure 5.1) and mapped. After a prolonged and in-depth survey of each haat/bazaar, a painstaking information has been extracted. Based on the operational day’s transaction, the amount has been grouped (Figure 5.2). The two most significant markets that generate a daily transaction of more than Rs. 1000, 000/- were observed to be the Jhalda Haat and the B. N. Singhdeo Bazaar. The Jhalda Haat generates more than Rs. 3000, 000/. Tulin Haat and Torang Bazaar generate transaction amount somewhere between Rs. 500, 000/ to Rs. 1000, 000/. The Jargo Haat and Bandulahar Haat generate transactions between Rs. 200, 000/- to Rs. 500, 000/. About 19% generate a daily transaction between Rs. 100, 000/- to Rs. 200, 000/- which include Maru Haat, Ananda Bazaar, Bandhaghat Bazaar, Brajapur Monday Haat

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 368

ISSN 2229-5518

and Brajapur Friday Haat. Approximately, about 11% of the haats/bazaars including Jhalda Municipal Bazaar, Kalma Haat and Kanshidih Haat generate transaction between Rs. 50, 000/- to Rs. 100, 000/. Baragrambagan Haat, Jargo Bazaar, Ichag Bazaar and Birudih Bazaar are among the 15% of the haats/bazaars to generate transaction of about Rs. 25, 000/- to Rs. 50, 000/. Approximately, 23% of the block’s haats/bazaars generate a daily transaction of Rs. 10, 000/- to Rs. 25, 000/- which include the haats/bazaars Mosina Bazaar, Piprajara Haat, Mahatmara Haat, Goria Haat, Iloo Bazaar and Dumurdih Haat. Patub Haat and Hesahatu Haat generate a daily transaction of less than Rs. 10,

000/.

Figure 5.2: Occurrences of haats/bazaars in each transac- tion group

Various particulars of the surveyed haats/bazaars related to general information, trade particulars, location aspects and infrastructural facilities have been enumerated in the following section. The general information regarding the operating days, nature of the markets, auction amount and transaction have been provided in Table 5.1. Based on the operational days the ten rural markets of the block could be categorized into daily markets (bazaars) and 16 as periodic markets (haats). Out of the twenty-six rural markets, only Jhalda Haat and Torang Bazaar were found to be involved even in wholesale trading.

Table 5.1: General information of the haats/bazaars

In the following section, the location particulars of the

haats/bazaars have been addressed (Table 5.2). It was well said, that the progress of a society lies with the development of communication. The existence of these haats/bazaars could be well credited to their location along metalled roads. This makes sure the ease of access by the visitors. However, the accessibility conditions, due to impact of the monsoon perils often cause trouble.

Table 5.2: Location aspect of the haats/bazaars

In the following section, the trade particulars of the haats/bazaars have been addressed (Table 5.3). The absence of permanent structured shops except for the Jhalda Municipality Bazaar may raise doubts as to how the markets operate then. The vendors seldom wait for any such facilities. All they need is a vacant place to sit, sometimes on bare ground or often on a piece of ragged jute cloth or plastic sheet. All that matters to them is to get a place, spread their goods, trade them, enjoy the haat day, interact with other local people. It is overwhelming to watch how despite facilities, these haats/bazaars attract such a huge crowd.

Table 5.3: Trade particulars of the haats/bazaars

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 5, Issue 12, December-2014 369

ISSN 2229-5518

The basic necessities of any human society that nurture in and around a market area first and foremost include adequate shelter for the vendors as well as the buyers, hygienic aspects of toilets, potable drinking water and proper disposal units. For a rural market to draw more crowds, which mean more transaction, the availability of electricity in the market area is compulsory. Moreover, to reduce the storage losses of the vendors, proper godown facility is necessary. It is evident that the facilities mentioned above and associated with the growth and development of existing rural agricultural markets have been simply absent when it comes to the haats/bazaars of Jhalda I block. Proper toilet facilities were only available in B. N. Singhdeo Bazaar and Jhalda Municipality Bazaar. Potable water and electrified shops were available only in the Jhalda Municipality Bazaar. Strangely, none of the twenty-six haats/bazaars have any facility of adequate storage and proper disposal units. This sorry state of affairs only raises concern and astounds how inspite of so much dearth the haats/bazaars still operate with full vigor and flavor.

After an analysis of all the parameters, it was highlighted that the potency of a haat/bazaar could be reflected in terms of its monetary transaction. This reflection was a collective response of all the studied parameters. The low transaction amount in the Patub Haat can be traced back to limited visitors whom the haat attracts. This limitation resulted due to the lack of proper locational and communication facilities as well as infrastructural facilities. If this state continues, the future of this haat does not seem to be very bright. It may unfortunately face the same fate of extinction, unless paid attention to when it is needed most. However, in the case of Mahatmara Haat, although the same factors could be held responsible for its low transaction, yet it must be considered that the haat has just revived from a dormant stage, hence it would need sufficient time to grow and establish itself. The Tulin Namopara Haat lost its glory due to extreme proximity to Tulin Haat, which is held just less than half a kilometer away. It was encouraged by the poor road condition beyond Tulin Haat, which was too unfavorable to support access to the former haat. There were sufficient reasons for the success of the existing haats/bazaars. The better the approachability through metalled roads to a market, the more were the expected buyers. The more the buyers, the more was the transaction. The strategic location and improved connectivity were the cornerstones for the opu- lence of the haats/bazaars. However, a bunch of complexities often plagued the rural agricultural markets. Eventually, com- bination of too much of these complexities leads to a slow death and ultimate extinction of a prominent haat/bazaar. It was observed that a haat/bazaar lost its glory only when it lost its horde to sell or buy. This was due to various factors like inaccessible roads, inadequate transportation, interior location away from metalled road, low zone of influence (buffer distance from where visitors arrive) and finally, lack of infrastructural facilities.

6 CONCLUSION

The haats/bazaars cater to the basic needs of the agricultural producers and consumers by providing them with both eco- nomic as well as social services. These services encompass the marketing of agricultural products along with arrangements for the inputs that are fundamental for agricultural produc- tion, thereby having a direct impact on the productivity. The rural agricultural markets can also be credited to exert an indi- rect impact on the productivity by acting as centres of social gatherings, which happen seldom in rural areas. These interac- tions are the sole medium of transfer of technology, through exchange of views. These markets are a “social nexus”, speak- ing the language of exchange and negotiation. The haats/bazaars of West Bengal have since centuries provided such linkages and villages have never suffered from the men- ace of isolation. Haats/bazaars are part of a system of markets that bound villages into localities and small communities into larger ones. They are the locus of activity for the indigenous society. They play an important role in maintaining growth of the agricultural sector. Thus, their status is a universal param- eter to judge the well-being of rural population. Hence, this particular study to identify the reasons behind the fluctuations in the status of any haat/bazaar seems to be justified, as their health is the prime indicator of the development of the rural sector. As long as they are affected by such bottlenecks, their functioning in the overall development of the rural sector will continue to be jeopardized.

REFERENCES

[1] Ahmed Z. 2010. Role of local government in indigenous market management in the rural areas of Bangladesh: Do these markets play de- velopment roles? Journal of Sustainable Development. Vol 3, No. 1, March

2010. 120 - 135.

[2] Khan A. Z. and Akther M. S. 2000. The role of growth centres in the rural economy of Bangladesh in Seraj, S. M., Hodgson, R. L. P. and Ahmad, K. L. (eds.). Village infrastructure to cope with the environment, Nov – Dec, 2000. The Proceedings of H & H 2000 Conference, Dhaka and Exeter.

[3] Wanmali S. 1981. Periodic markets and rural development in

India. (Delhi: B. R. Publishing Corporation, 1981).

[4] World Bank. 2008. “India Country Overview 2008."

[5] Yule H. and Burnell A. C. 1968. Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases (1903; reprint, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1968), 75-76.

IJSER © 2014 http://www.ijser.org