population are shown in Fig-1.

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1523

ISSN 2229-5518

By

ALI M BARAKAT MSc PhD1 , OLLI LAPAHATI 2 MD PhD HASSAN J HASONY MSc PhD1

1 Department of Microbiology, Basrah University, Medical College Basrah, IRAQ

2 Haartman Institute, Department of Viral Zoonoses, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, FINLAND

E-mail: drhassanjaber@gmail.com

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1524

ISSN 2229-5518

6.4%. Mostly this virus associated with CNS infections with 5.1% LCMV-RNA detection in CSF and reporting the first registration of LCMV-Iraqi strain in southern Iraq.

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1525

ISSN 2229-5518

According to the International Classification for Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Arenaviridae currently includes 22 viruses classified into two monophyletic complexes, Old World and New world1 on the basis of geographic, genetic and host relationships2. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is the only Arenaviridae member showing the worldwide distribution due to its association with cosmopolitan rodent species Mus musculus while all other members are geographically restricted3. Epidemiological studies showed that up to

11% of wild mice can be infected with LCMV4. Infected mice can shed virus

throughout their life5.

Severe human disease caused by Arenaviruses related to LCMV , Lassa fever virus and the newly discovered Luijo virus6. In Europe the prevalence of LCMV detected in Mus species ranged from 3.6% to 11.7%4 while in Asia the LCMV prevalence in mice ranged from 7% to 25% especially in Japan7.The mechanism of LCMV transmission to human is not fully understood, but may involves exposure to dust contaminated with rodent urine, contaminated food and drinks ,via skin abrasion or through direct contact with infected rodents or by inhalation of infectious rodent excreta or secretion during occupational exposure (laboratory workers, rodents sellers or breading8. Recently detected that transplant recipients may become infected from chronically infected donors9.

The overall rates of human exposure to LCMV are not known. Two large surveys in the USA suggested that 3-5% of the study individuals had LCMV- IgG10,11. The seroprevalence of LCMV infections was 1.3% in Spain12, Canada 4%

13 and Argentina was 2.38% 14. Other studies on LCMV infections reported higher

seroprevalence of 17.7%15; but in Italy was 2.5% 16, and in England was 1%17.

Human infections can range from mild, flu-like febrile illness to severe encephalitis, aseptic meningitis and disseminated disease8. The meningeal form is more common and in some cases severe meningoencephamyelits leading to death, and infections during pregnancy may cause abortion or congenital malformation8. In severely affected individuals endothelial cell damage causes erythrocytes and platelet dysfunction, which leads to increased vascular permeability, capillary leakage and altered cardiac function. Cytokines and other soluble mediators may

contribute to the pathogenesis of the dysfunction in vascular endothelium18.

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1526

ISSN 2229-5518

This study was designed to investigate LCMV seroprevalence in southern Iraq and molecular detection and specification of LCMV isolates from serum and CSF from patients with acute febrile illness and neuroinvasive cases. MATERIALS AND METHODS

82 years) in Al-Nasiriyah Governorate, southern Iraq, during the period from February 2012 to October 2013.The specimens were obtained from patients with acute febrile illness and CNS symptomatic patients (n= 178), symptomatic patients with associated chronic diseases (n=152) which was previously diagnosed by clinicians in Al-Hussain Teaching Hospital and Bint-Al-Huda maternity and Children Teaching hospital and asymptomatic healthy individuals (n=155) that obtained from medical staff, blood donors and student volunteers. All required informations were obtained on special questionnaire form after taking verbal consent from all participants. Venous blood (5ml), CSF (2ml) or urine (5ml) was collected and stored at – 45C (at blood bank center in Al-Nasiriyah). Specimens were shipped on dry ice by airplane to the department of viral zoonoses laboratories , Haartman Institute, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Finland and stored at – 80C until uses for IFA (Immunofluorescent test). ELISA (Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and RT- PCR (Reverse transcriptase –polymerase chain reaction).

Vero E6 cells cultured for 4 days until become confluent, inoculated with LCMV (obtained from viral zoonoses laboratories at Haartman Institute, Helsinki, Finland). Infected cells were divided into 10 wells slides and dried in a laminar flow cabinet, then fixed with acetone for 7 minutes and air dried then stored at –

70C until use for IFA. Serum samples and controls were diluted 1:20 with PBS. IF staining procedure and scoring of IFA positivity was followed according to standardized method19 used conventionally in the viral zoonoses laboratories. MOLECULAR DETECTION OF LCMV:

Viral nucleic acid was extracted from 200ul of serum (n=139), Samples of CSF from neuroinvasive cases were tested by conventional PCR assay for detection of LCMV – RNA using QIAamp viral RNA Mini Spin kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol through the use of

LCMV Old world strain specified set of primers:

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1527

ISSN 2229-5518

Virus | Primer | Sequence | Nucleotid position | Reference | |

Old-world Arenavirus | LVL_D_Y+ | 5-AGAATCAGTGAAAGGGAAAGCAAYTC-3 | 3359-3332 | (Vieth et al 2007)20 | |

Old-world Arenavirus | LVL_G_Y+ | 5-AGAATTAGTGAAAGGGAGAGTAAYTC-3 | 3359-3332 | (Vieth et al 2007)20 | |

Old-world Arenavirus | LVL_A_R- | 5-CACATCATTGGTCCCCATTTACTATGRTC-3 | 3754-3724 | (Vieth et al 2007)20 | |

Old-world Arenavirus | LVL_D_R- | 5-CACATCATGGTCCCCATTTACTGTGRTC-3 | 3754-3726 | (Vieth et al 2007)20 |

Y=C or T, R=G or A

Total RNA was converted to cDNA using a single step kit (Superscript II One-step RT-PCR: Invitrogen, UK) The cDNA generated by reverse-transcription and amplified by conventional PCR.

1000 bootstrap replicates21.

Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version-15 software was used to analyze data. Chi-square (X2) test was used to assess the significance of differences between groups. P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1528

ISSN 2229-5518

The seroprevalence of LCMV-IgG as tested by IFA is presented in table-1. The overall serprevalence among study population was 6.4% (12/178) of LCMV- IgG was found in 5.1% (8/155) of asymptomatic healthy individuals. The differences between these groups was statisticall not significant (P>0.05).

X2 =0.61 df= 2 P > 0.05

The seropositivity to LCMV-IgG in relation to gender, age and area of residence is summarized in table-2 . LCMV antibodies were found in 3.5% of men and among 9.7% of women. The prevalence LCMV-IgG are increased as the age of individuals increased as its 1.6% (2/123) in the youngest age group (1-30 years) , 6.7% (16/236) among age groups of 31-50 years and 10.3% (13/126) in the older age group (51-85years). The differences between these age groups was statistically significant (P<0.05). However, residents of urban areas showed higher rates of LCMV –IgG seropositivity (10.1%) and to less extent among rural areas (4.4%). The difference was statistically significant (P <0.05).

Variable | LCMV - IgG | P- value | |

Variable | No. +ve/ No. tested (%) | P- value | |

Gender | Women | 22 / 226 (9.7) | <0.05 |

Gender | Men | 9 /259 (3.5) | <0.05 |

Age (years) | 1 - 30 | 2 / 123 (1.6) | <0.05 |

Age (years) | 31-50 | 16/ 236 (6.7) | <0.05 |

Age (years) | 51-85 | 13/126 (10.3) | <0.05 |

Area of residence | Urban | 17 /167 (10.1) | <0.05 |

Area of residence | Rural | 14 /318 (4.4) | <0.05 |

Total | 31 / 485(6.4) |

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1529

ISSN 2229-5518

Table-3 shows the geographic distribution of LCMV-IgG positive cases. The highest seroprevalence (10.1%) was found in the city centre region, followed by Al-Shatra region (6.1%), Suq Al-Shuyuk (4.2%), Chebayesh (3.2%) and Al-Refaey region (3.1%).

Geographic areas | LCMV- IFA-IgG |

Geographic areas | No. +ve / No. tested (%) |

City centre | 17/ 168 (10.1) |

Al-Shatra | 6 /98 (6.1) |

Suq Al-Shuyuk | 4/95 (4.2) |

Chebayesh | 2/61 (3.2) |

Al-Refaey | 2/ 63 (3.1) |

Total | 31 /485 (6.4) |

Molecular detection of LCMV from the samples collected from study

population are shown in Fig-1.

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1530

ISSN 2229-5518

None of RNA extracted from blood or urine specimens showed positive results for LCMV-specific genomic RNA. However, by the use of conventional RT-PCR assay on 39 CSF specimens , LCMV was found among neuroinvasive cases in a rate of 5.1%. The agarose gel electrophoresis results showed that a target fragment was amplified by RT-PCR in the RNA extracted from CSF of two patients with meningitis (Fig.1). The PCR products for the two CSF positive samples was confirmed by sequencing through the use of modified Sanger sequencing method and an ABI Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The results of genome sequences are shown in Fig-2 :

AGAATCAGTGAAAGGGAAAGCAATTCTGAGTCTCTAAGCAAGGCTTTG

TCCTTAACTAAGTGTATGAGCGCAGCATTAAAAAACTTGTGTTTCTATT CTGAAGAATCCCCAACTTCATATACCTCAGTTGGCCCTGACTCTGGGAG

GTTAAAGTTTGCGCTGTCCTACAAAGAACAAGTTGGAGGCAATAGGGA ACTTTATATTGGAGACTTGAGGACAAAGATGTTTACAAGGTTAATAGA AGACTACYTTGAATCTTTTGCCAGCTTTTTTTCAGGATCATGTTTAAATA ATGAAAAGGAATTTGAAAACGCAATTCTCTCAATGACCATCAATGTGA GGGAAGGGTTCTTAAATTATAGCATGGAYCAYAGTAAATGGGGACCAA TGATGTG

GAATCAGTGAAAGGGAAAGCAATTCCGAGTCTTTAAGCAAGGCTTTGT

CCTTAACCAAGTGTATGAGTGCAGCATTGAAAAACTTGTGTTTTTATTC TGAAGAATCTCCAACCTCATACACCTCAGTTGGCCCTGACTCTGGGAGG TTAAAGTTTGCGCTGTCCTACAAAGAACAAGTTGGAGGCAATAGGGAA CTTTATATTGGCGACTTGAGAACAAAGATGTTTACAAGGCTGATAGAA GATTACTTTGAATCCTTTGCTAGCTTCTTCTCAGGATCATGCTTGAATAA

TGAAAAGGAGTTTGAAAACGCAATCCTCTCAATGACCATCAATGTAAG AGAAGGGTTTCTAAATTATAGCATGGAYCAYAGTAAATGGGGACCAAT GATGTG

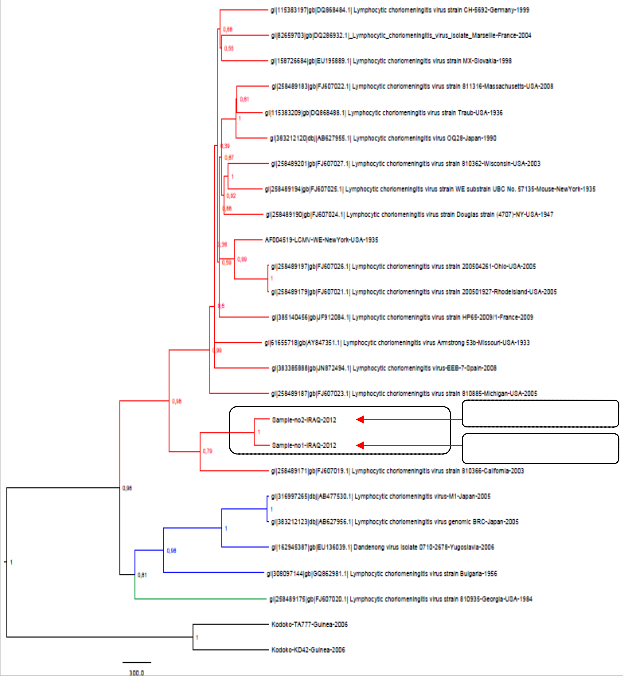

Results of phylogenetic analyses performed on the LCMV complete genome are shown in Fig-3. The topologies observed in the phylogram confirmed that these two isolates had 93.4% similarity with each other, but distinct from other known LCMV strains. The LCMV sequence from Iraqi CSF samples, sample no. 1 –

IRAQ 2012 had 83.2% and the sample no. 2 had 83.9% identity with LCMV-

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1531

ISSN 2229-5518

810366-California strain (FJ607019) isolated from USA during 2003. The phylogenetic status of the sequence of Iraqi LCMV strain was assessed by the

Neighbour-Joining algorithm in MEGA-5.

Iraq isolate no. 1

Iraq isolate no. 2

![]()

Figure-3: Phylogenetic tree based on a sequence of LCMV strain generated by

using the neighbor –Joining algorithm in MEGA-5 .

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1532

ISSN 2229-5518

Studies in endemic areas showed a seroprevalence range of 1-10% for LCMV15. Other studies detect the prevalence of LCMV antibodies of 1.7% from Spain22, the Netherland 2.9%23, France 0.33%24, and 3.5-5% in USA25. The detection of anti-LCMV antibody in Iraqi human sera revealed high seroprevalence (6.4%) in the population of southern Iraq, which is much higher than that reported from most regions mentioned above as these viruses are rodent-borne and the area of marshes in southern Iraq is highly invested with these vectors implying the needs for a good surveillance and investigational program from the local health authorities. However, epidemiologic studies showed a seroprevalence to LCMV reaching 11% among mice infected with LCMV 4 and these infected vectors can shed LCMV throughout their life5.

The results of this study refer to higher LCMV seropositivity among women compared to that observed in men may be due to frequent exposure or inhalation of house dust that contaminated with the excreta of house mice an observation similar to that reported by some studies8. On the other hand the intensity and crowdness in the city may explain the increased LCMV positivity among the urban population. Recent studies showed that LCMV may have become chronic in asymptomatic form9 which may pose a real threat for affected individuals because members of this virus group (Arenaviruses) are very well known be implicated in a variety of severe human disease including hemorrhagic manifestation as Lassa fever virus infection12,18.

Beside the investigation of the LCMV prevalence in the area, this study was designed to determine the role of LCMV as a causative agent in patients with neuroinvasive diseases by using PCR as more sensitive and specific technique. Although this is the first study investigating the circulation of LCMV where serologic data from this study showed an overall seroprevalence of 6.4% in southern Iraq, LCMV-RNA genome was detected in 5.1% of CSF samples by PCR referring to the association of LCMV with CNS manifestations rather than other types of infection. This observation is consistent with that reported from

Japan7. As one of this study objectives was to investigate the presence of known or

potentially new Arenaviruses in human CSF during neurological diseases and to characterize them through complete LCMV genome sequencing and phylogenetic

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1533

ISSN 2229-5518

analysis. Evidence based on genetic analysis of human LCMV strains was not previously available in Iraq. In this study, RT-PCR was used to detect LCMV infection rate in neuroinvasive patients, which was found in 5.1%, suggesting that LCMV is a common aetiology of CNS infection in the region. These findings were confirmed by sequencing the PCR products which indicates that LCMV strain (isolates of Iraq) are a new registered for the first time as Iraqi strain and has its position in the phylogenetic tree worldwide. The sequence of PCR products obtained was most closely related to the sequence of lineage-I. Sequence homology among the LCMV amplicon from CSF Iraqi specimens detect that LCMV Iraqi isolates 1 and 2 had 93.4% similarity with each other (i.e. 26 out of

394 nucleotides were different). The sample no. 1 had 83.2% and the sample no. 2 had 83.9% identity with LCMV strain 810366 (FJ607019) isolated from USA in California during 2003 (present in Gene Bank). PCR and sequencing methods are useful because it allowed genetic analysis of the LCMV strain from neuroinvasive cases. The isolated strain fro this study belonged to classical lineage –I which has been usually associated with human diseases (as are lineage II and III) and is linked to common house mouse as its reservoir10, that commonly found in the marshes areas.

In conclusion , LCMV is serologically present in the area with a prevalence of

6.4%. Most of LCMV cases associated with CNS involvement as the LCMV-RNA genome was detected in 5.1% of neuroinvasive patients. The detected LCMV- Iraqi isolates 1 and 2 had 93.4% similarity with each other (i.e. 26 out of 394 nucleotides were different). The sample no. 1 had 83.2% and the sample no. 2 had

83.9% identity with LCMV- 810366- California strain (FJ607019) isolated from USA during 2003, that imply the consideration of LCMV as CNS pathogen in clinical practice.

1. Palmer SR, Soulsby L, Torgerson P, David W, Brown G. Oxord Textbook of Zoonoses : Biology, Clinical practice and public health control. Oxford University Press 2011, 14 pp 283-310.

2. Buchmeier MJ, Peters CJ, de la Torre JC. Arenaviridae: the viruses and their replication. Field Virology, 5th ed vol-2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins ;

Philadelphia PA 2007.

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1534

ISSN 2229-5518

3. Charrel RN, de Lamballerie X, Emonet S. Phylogeny of the genus Arenavirus.

Curr Opin Microbiol 2008, 11 : 362-368.

4. Lledo L, Gegundez MI, Bahamontes N, Beltran M. Lymphocytic

Choriomeningitis virus infection in a province of Spain: Analysis of sera from the general population and wild rodents. J Med Viol 2003,70:273-275.

5. Emonet S, de la Torre JC, Domingo E, Sevilla N. Arenavirus genetic diversity

and its biological implications. Infect Genet Evolution 2009, 9: 417-429.

6. Briese T, Paweska JT, McMullan LK, Hutchison SK,Street C,Palacios G et al.

Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever associted Arernavirus from south Africa. PLOS Pathog 2009,5(5): E1000455.

7. Toshikazu t, Makkiko O, Chiharu M, Hiroshi S, Kazutaka O. Genomic analysis and pathogenic characteristics of Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus strains isolated in Japan. J Comparative Med 2012, 62(3): 185-192.

8. Barton LL, Hyndman NJ. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus; Remerging

Centeral nervous system pathogen . Pediatrics 2000, 105: E35

9. Fischer S, Graham MB, Kuehnert MJ. Transmission of Lymphocytic

Choriomeningitis virus by organ tansplantation. New Eng J Med 2006,

354: 2235-2249.

10. Diaz JH. Global climate changes, natural disasters and travels health risks.

J Travel Med 2006, 13 : 361-372.

11. Kawaguchi L, Sengkeopraseuth B, Tsuyuoka R, Koizumi N, Akashi H, Vongphrachanh P, et al. Seroprevalence of leptospirosis and risk factor Analysis in floodbrone rural area in Lao PDR. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008,

78 : 957-961.

12. Mercedes PR, Navarro-Mari JM, Sanchez-Seco MP, Gegundez MI, Palacios G, Savji N, et al. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-associted meningitis, Southern Spain. Emerging Infect Dis 2012, 18(5): 855-858

13. Thomas JM and Saron MF. Seroprevalence of lymphocytic choriomeningitis

Virus in Nova Scotia. The Am Soc Trop Med Hyg 1998,58(1): 47-49

14. Ambrosio AM, Feuillade MR, Gamboa GS, Maiztegui JL. Prevalence of Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection in a human population of Argentina . Am J Trop Med Hyg 1994, 50 : 381-386.

15. Duh D, Varljen-Bazan E, Hasic S, Charrel R. Increased seroprevalence of

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection in mice sampled in illegal

Waste sites. Parasites and Vectors 2014, 7(1): O31

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 4, April-2015 1535

ISSN 2229-5518

16. Kallio-Kokko HJ, Laakkonen A, Rizzoli V, Tagliapietra I, Cattadori S, Perkins E, et al. Hantavirus and Arenavirus antibody prevalence in rodents And human in Trentino, northern Italy. Epidemiol Infect 2006, 134: 830-836

17. Michele TJ, Glaser C, Charles F. The Arenaviruses . JAVMA 2005, 227 (6):

904-915.

18. Peters CJ. Arenaviridae : Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, Lassa virus and The south American hemorrhagic fevers, In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R Mandell eds, Douglas and Bennett’s principle and practice of infectious Diseases. 7th ed, Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone 2010, pp 2295-2301.

19. Wong S, Valerie L, Rebekah H, Tian W, Michel L, Kalipada K, et al. Detection of Human Anti-Flavivirus Antibodies with a West Nile Virus Recombinant Antigen Microsphere Immunoassay. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;

42 (1): 65-72.

20. Vieth S., Drosten C., Lenz O., Vincent M., Omilabu S., Hass M., et al. RT- PCR assay for detection of Lassa virus and related Old World arenaviruses targeting the L gene. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg., 2007; 101:1253–1264.

21. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA-5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, Evolutionary distance and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol

2011, 28 : 2731-2739.

22 . Kleinman S, Caulfield T, Chan P. Toward an understanding of transfusion- Related acute lung injuries: statement of a consensus panel. Transfusion

2004, 44 : 1774 -1789.

23. Zhou L, Giacherio D, Cooling L, Davenport RD. Use of B-natriuretic peptide As a diagnostic marker in the differential diagnosis of transfusion associated Circulatory overload. Transfusion 2005, 45 : 1056 -1063.

24. Eberhard W, Alan HB, Janes K, Julian T, Kim-Anh T, Toy P. Prevalence of Antibodies to Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in blood donors in Southeast France. Transfusion 2007, 47 : 172-173.

25. Clerico A, Del-Ry S, Giannessi D. Measurement of cardiac natriuretic Hormones (atrial natriuretic peptide, brain natriuretic peptide and related Peptides) in clinical practice: the need for new generation of immunoassay

Methods. Clin Chem 2000, 46 : 1529-1534.

IJSER © 2015 http://www.ijser.org