International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 7, July-2013 1650

ISSN 2229-5518

Assessment of Livelihood Strategies among Households in Forest Reserve Communities in Ondo State, Nigeria

A.S. Aruwajoye, I. A. Ajibefun

Index Terms— , Assessment, , forest reserve communities, forest resources,households, livelihood strategies,multinomial logit,natural resources.

—————————— ——————————

t has long been stated within Nigeria and internationally, that forests (in the broadest sense of the word, which in- cludes savannas and plantations) offer numerous benefits to adjacent communities and society at large [1]. Such benefits include consumptive resources, spiritual and aesthetic needs, employment generation, and ecological services such as car-

bon sequestration and water provision.

Forests provide home and livelihood for people living in and around them and serve as vital safety nets for the rural poor. In Nigeria, forest resources are being depleted at alarming rates due to overexploitation.

Over two-thirds of Africa’s 600 million people rely di-

rectly and indirectly on forests for their livelihoods, including food security. Wood is the primary energy source of at least

70% of households in Africa [2].

Forest communities are largely agrarian but rely heavily on

forest resources as a source of livelihoods. People living in

these forest communities depend on products from the forest for a variety of goods and services. These includes collection of edible fruits, flowers, tubers, roots and leaves for food and medicines; firewood for cooking (some also sell in the market); materials for agricultural implements, house construction and fencing; fodder (grass and leave) for livestock and grazing of livestock in forest; and collection of a range of marketable non-timber forest products. Therefore, with such a huge population and extensive dependence pattern, any over ex- ploitation and unsustainable harvest practice can potentially degrade the forest. Moreover, a significant percentage of the country’s underprivileged population happens to be living in its forested regions [3]. The majority of forests, by their very nature, are located within rural and frequently remote areas. Typically this means that such areas are underdeveloped in

terms of infrastructure, government services, markets and jobs. It is not surprising, therefore, that communities living in and adjacent to savannahs and forests are characterised by seemingly high levels of poverty and limited livelihood op- portunities [4].

The long-term contribution of forest resources to the livelihood strategies of the rural poor had long been appreci- ated as significant [5],[6],[7],[8]. In the forestry context, forest or trees resources that the rural poor can freely access might form a critical part of their lives. A primary role of forest or tree resources in the lives of the rural poor is thus as a “safety net”, as one of many strategies to avoid falling into destitution [9]. In the context of Africa, forests are vital for the welfare of millions of people, especially the rural poor and marginalised, and their wise use could improve livelihoods and quality of life.

Although, biodiversity and tree based assets are un-

dervalued in national statistics and accounting, and grossly under-invested in development decision making, the potential contributions of forests to the national economy cannot be over emphasized. [10] stated that some researchers have re- ported the potentials of tree and animal species in the forest ecosystems and over 150 indigenous woody plants have been noted for their edible products for human and livestock con- sumption. It is estimated that more than 15 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa earn their cash income from forest-related enterprises such as fuelwood and charcoal sales, small-scale saw-milling, commercial hunting and handicraft. In addition, between 200,000 and 300,000 people are directly employed in the commercial timber industry [11].

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 7, July-2013 1651

ISSN 2229-5518

The population of the study was made up of community members from selected forest reserves in Ondo State. They are Oluwa forest reserve and Owo forest reserve.

A multi-stage sampling technique was used to select the study

area based on size, tree specie richness and high rate of eco-

nomic activities in terms of forest resources exploitation. Two forest reserves were purposively selected which are Owo for- est reserve and Oluwa forest reserve in Owo and Odigbo LGAs. 60 respondents were randomly selected from each re- serve; thus making a total of 120 respondents.

Primary data were collected and used for the study with the

aid of structured questionnaire which was administered to

obtain information for the study. The structured interview schedule covered four sections namely; socio economic char- acteristics of the respondents, data on community livelihoods, forest resources exploitation, production and productivity.

Descriptive statistics were used to examine socio-economic characteristics of the respondents such as age, household size, gender, marital status, educational level, farming experience, farm size, household income, household domestic energy, type of crop enterprise, sources of labour used, distance to market and access to health centre; resources available to households and major livelihood strategies among households in the study area. Multinomial logit regression analysis was therefore used to analyze factors influencing respondents’ choice of livelihood strategies in the study area. The depend- ent variables were major livelihood strategies while explana- tory variables were socioeconomic characteristics.

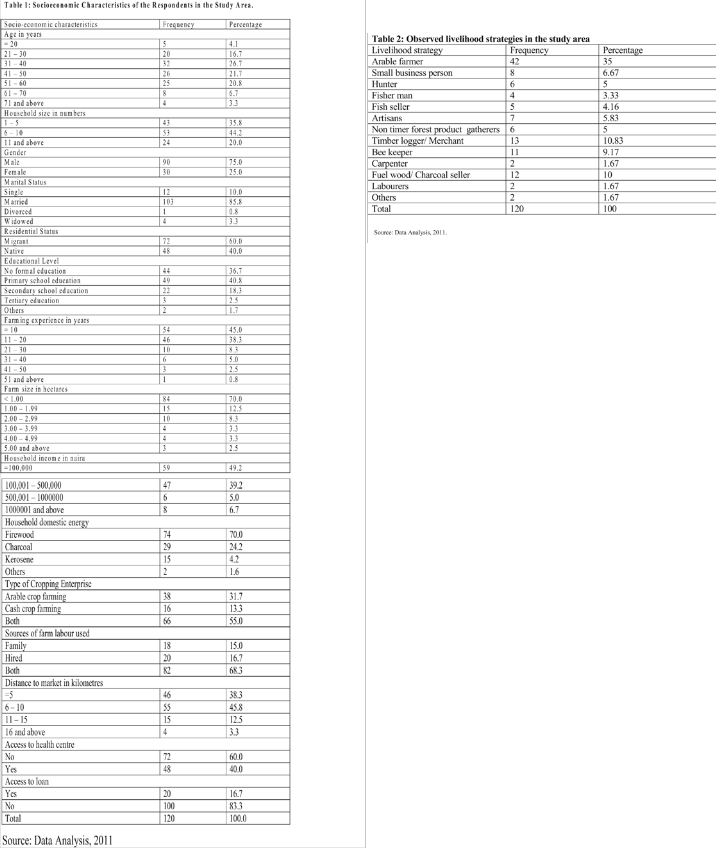

The respondents socio-economic characteristics analysed for this study were age, marital status, household size, farming experience, gender, access to credit, educational level, farm size, sources of farm labour used,type of cropping enterprise, household income,household domestic energy,distance to market,access to health centre.

A total of 120 respondents were interviewed using

quantitative questions. Table 1 shows that the modal class is

31-40years while the mean age of the respondents was 43.30

years, this shows that that population is active and that the older farmers have younger farmers who could replace them when they can no longer farm. There was an average number of 7 persons per household.

The findings revealed that 75% of the respondents were males while 25% were females which implies that males dominated

the farming occupation in the study area and this has been in line with many studies carried out in Ondo State. It was also shown that over 85% of the sampled respondents are married which implies that most of the respondents were mature and responsible to cater for their households as well as have clear knowledge of their wellbeing. A considerable 60% are mi- grants to the area only 40% are born in the community. In

both areas, education levels are low for the majority of the communities. An overwhelming 77.5% of respondents either have had no education at all or only have primary level edu- cation to different degrees. 1.7 % was educated to Standard six. The reason for this has been a lack of insufficient educa- tion facilities in the past and difficulty accessing education in the rural areas. The mean year of farming experience is about

19 years indicating that the farming households had spent a

good number of years on farming practices.it is generally

believed that the more the years the farmer the better the

ability for such farmer to make decisions. Majority of the

respondents (38.3%) fall in year bracket of 11 and 20 and only one respondent has been farming for over 51 years in the study area. The farm size still confirms the peasant nature of the farmers in the study area where majority of the respondents (90.8%) farmed on less than 3ha of land with the mean farm size of 1.14ha Income has been a vital tool in accessing human wellbeing About 93.4% of the sampled households earn less than N100,000.00 per annum, while only eight respondents earned over a million in the last season. This shows that respondents depend on forest products as they derive their source of income from the sale of its products.The average household income was N258,631.67. Majority of the respondents (94.2%) use firewood or charcoal as their household domestic energy, 4.2% use kerosene while

1.6% were others who use other sources for their domestic energy. This clearly indicates a very strong dependence of the

people on the forest resources for domestic energy. The study further gave insight to the type of farm enterprise ventured into in the study area using multiple responses. It was revealed that the respondents who cultivated arable crops were 31.7%, 13.3% of them cultivated cash crops, while 55.0% cultivated both cash crops and arable crops. The table shows that 15.0% used family labour, 16.7% claimed they used hired labour while most 68.3% used both family and hired labour. Some of the farmers hired labourers to work on their farms and also used their family members as well. Farmers who had a larger expanse of land used both sources of labour. Here, those who had a larger household size had an advantage in the case where they could use their family members to work on their farms in the study area. The table also shows that

38.3% of the respondents do not need to go too far to the near- est market as they had to move through a distance of less than

5km to sell their products, 61.7% of the respondents had to move through a distance above 5km. Forest products which are sold very near to the market were cheaper than those which were sold far from the market. It was shown that 53.5 % had access to health centres while 41.7% had no access to health centres and used the herbs as a form of treatment.

A good number of the household (83.3%) had no access to loan, 16.7% had access to loan from friends or relatives. Access to microcredit in rural areas is difficult. The vast majority who do not have no access to credit or do not know how to access it was because of the distance from the institutions, lack of awareness, high interest rates, lack of groups being formed to share loans together and lack of collateral, as well as scare stories about people losing everything when they are unable

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 7, July-2013 1652

ISSN 2229-5518

to pay, make many respondents sceptical about success.

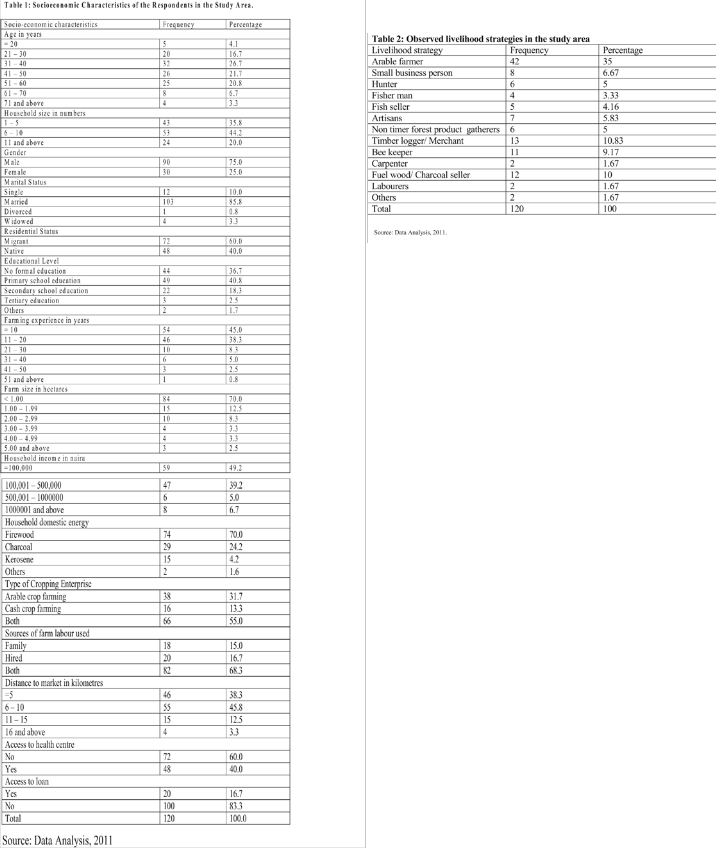

The observed livelihood strategies in the study area are pre-

sented in Table 2. A good number of the respondents (35%) were farmers, this shows that the respondents are predomi- nantly farmers,it is also an indication of encroachment be- cause they are not meant to farm in the forest reserves. 10.83% were timber loggers showing that logging activities are still being carried out but by only few people this may be due to the level of degradation in the forest area, 10% were fuelwood sellers, the percentage of these respondents can be increased if those living in the communities are actively involved in com- munity based forest management and agroforestry, 9.17 were beekeepers 6.67% were small business persons( petty trad- ers),5.83% were artisans, 5% were hunters the hunters were few and this may be because a lot of animals have gone into extinction,5% were non timber forest product gatherers, 4.16% were fish sellers,3.33% were fishermen,3.34% were labourers and carpenters others were palm wine tappers and farm pro- duce processors.

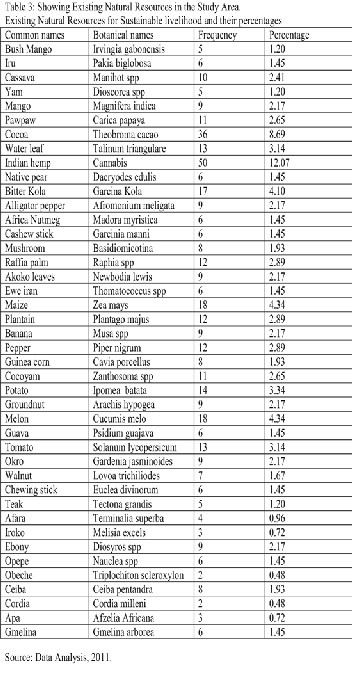

The existing natural resources identified in the study area are presented in Table 3 and they were food crops, cash crops, fruits, vegetables and tree species.They include Bush mango, Plantain, cocoa, cassava, yam, groundnut, banana, pineapple, vegetables, melon, guava, pear,cashew, tomato, okro, maize, pepper, mango, guinea corn, cocoyam, pota- to,groundnut,melon, pawpaw, ogbolo (Irvingia gabonensis), Water leaf (Talinum triangulare). and mushroom, kola, Indian hemp(Cannabis) ,sponge and chewing stick is peculiar to Owo

, oil palm and so on. Tree species that were identified include Lovoa trichiliodes, Euclea divinorum, Tectona grandis, Terminalia superba, Melisia excelsa, Diosyros spp, Nauclea spp, Triplochiton

scleroxylon, Ceiba pentandra, Cordia milleni, Afzelia Africa- na,Gmelina arborea and so on.

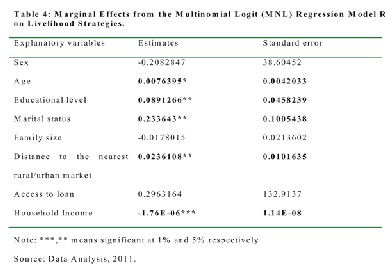

Multinomial logit (MNL) regression model was used for the analysis. The table above presents the estimated marginal ef- fects and standard error from the MNL model. The results show that most of the explanatory variables considered are statistically significant at 5%. This study uses farming liveli- hood as the base category for no livelihood strategy and eval- uates the other choices as alternatives to this option. The like- lihood ratio statistics as indicated by chi-square statistics (80.28) are highly significant (P< 0.0002), suggesting the model has a strong explanatory power. As indicated earlier, the pa- rameter estimates of the MNL model provide only the direc- tion of the effect of the independent variables on the depend- ent variable: estimates do not represent actual magnitude of change or probabilities.

Thus, the marginal effects from the MNL, which measure the

expected change in probability of a particular choice being made with respect to a unit change in an independent varia- ble, are reported and discussed.

Age of the respondent is positive and statistically significant in influencing household livelihood strategies in the study

area. A unit increase in the age of the respondent results in

0.7% increase in the probability of choosing other livelihood

strategies apart from farming. The educational level of the

respondent shows a positive coefficient and is significant at

5% level of probability. It means that the higher the level of

education of the respondent, the more the likelihood of choos-

ing other livelihood strategies apart from farming. A year in- crease in the years of education attained will increased the chance of engaging in other livelihood strategies by 8.9%. The marital status of the respondents has a positive coefficient and significant at 5% level of probability. It means that households who were married were 23.4% more likely to engage in other livelihood strategies apart from farming. The distance to the nearest rural/urban market is also statistically significant at

5% level of probability in explaining livelihood strategies among respondents in the study area. It means the longer the

distance to the market the more the chance of involving in different livelihood strategies. A unit increase in the distance (Km) to the market from the settlement results in a 23.6% in- crease of the probability of engaging in livelihood strategies other than farming. The household income was negative but significant at 1% level of probability in explaining the choice of livelihood strategies being undertaken by the respondents. It means that a unit increase in household income (Naira) re- sults in decrease in the likelihood of switching to other liveli- hood strategies other than farming. If Government takes steps to reduce the factors which put pressure on the forests such as actively encouraging and supporting investment in industrial development, deliberately supporting employment and alter- native income generating activities such as piggery, poultry, rabbitry, agroforestry, nursery practices and others, the re- spondents will be willing to switch to other livelihood strate- gies apart from farming.

The access to loan was not statistically significant but has a

positive coefficient. It can be inferred that it has a positive re-

lationship in explaining the kind of livelihood strategies cho-

sen by the respondents in the study area.

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 7, July-2013 1653

ISSN 2229-5518

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 7, July-2013 1654

ISSN 2229-5518

.

————————————————

• Prof.I.A Ajibefun is currently the Rector of Rufus Giwa Polytechnic.Km 40

Benin-Owo Expressway and Department of Agricultural Econom-

ics,Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria+2348034825338. E- mail: iajibefun@yahoo.com

In terms of livelihood strategies, it is evident that agriculture and forest resources are important contributors to rural liveli- hoods and household income. Many livelihood strategies were identified which includes arable farmers, small business persons (Petty traders), hunters, fisher men, fish sellers, arti- sans, non-timer forest product gatherers, timber logger/ Mer- chant, and so on. Although the forest reserves have been de- pleted but logging activities are still taking place. Non-timber forest products are collected within the communities but in reducing amounts. This means the safety nets are less availa- ble which makes the communities more vulnerable in terms of economic stress. Hunting also takes place in but in smaller quantities. Only few of the community members in were arti- sans.

The importance of fuelwood wood production is a major

source of forest income especially for those living around the forest reserves as many of the respondents depend on fuel- wood as a source of domestic energy. Therefore Government should takes steps to reduce the factors which put pressure on the forests such as actively encouraging and supporting in- vestment in industrial development, deliberately supporting employment and alternative income generating activities. There should also be massive reforestation and reforestation.

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 4, Issue 7, July-2013 1655

ISSN 2229-5518

[1] NFAP 1999. South Africa's National Forestry Action Programme. Dept of

Water Affairs & Forestry, Pretoria. Pp 92.

[2] CIFOR (2005). Contributing to African Development through Forests: strategy for engagement in sub-Sahara African. Centre for Interna- tional Forestry Research, Bogor, Indonesia. June, Pp. 34.

[3] Saha, A. and Guru,B.(2003). Poverty in Remote Rural Areas in India: A Review of Evidence and Issues, GIDR Working Paper No 139, Ahmedabad: Gujarat Institute of Development Research. Pp 69.

[4] Wunder. S. (2005) “Forestry and sustainable livelihoods”. World

Commission on Environment and Development (1999). Our Common

Future. Oxford University Press. Pp 1817.

[5] Salafsky, N. Wollenberg, E. (2000). Linking livelihoods and conserva- tion: A conceptual framework and scale for assessing the integration of human needs and biodiversity. World Development, 28(8): Pp

1421.

[6] Belcher, B. (2003).Global Patterns and Trends in the Use and Man- agement of Commercial Non Timber Forest Products: Implications for Livelihoods and Conservation. World Development Vol. 33, No.

9, Pp. 1435.

[7] Levang,P.,Dounias,E., and Sitorus,S. (2005). Out of the forest, out of poverty? Forests, Trees and livelihoods,15(2): Pp 230.

[8] Sunderlin, W. Angelsen, A. Belcher, B. Burgers, P. Nasi, R. Santoso, L.

and Wunder, S. (2005). Livelihoods, forests, and conservation in de- veloping countries: an overview. World Development, 33(9): Pp

1383.

[9] Shimizu, T. (2006). Assessing the access to forest resources for im- proving livelihoods in West and Central Asia countries. Livelihoods Support Programme. LSP Working Paper 33. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, FAO, Rome. Pp. 42.

[10] Adekunle, V.A.J (2005) Trends in Forest Reservation and Biodiversity Conservation in Nigeria. In: Environmental Sustainability and Conser- vation in Nigeria, Okonkwo, E, Adekunle V.A.J & Adeduntan, S. A. (Editors); Environmental Conservation and Research Team, Federal University of Technology Akure Nigeria, Pp 82.

[11] Oksanen, T. and Mersmann, C. (2003), “Forests in Poverty Reduction Strategies: An assessment of PRSP Processes in Sub-Saharan Africa”. In: Oksanen,T. Pajari,B., Tuomasjukka, T. (eds.). Forests in Poverty reduction Strategies: Capturing the Potential. EFI Proceedings No.

47:Pp121.European Forest Institute, Finland.

IJSER © 2013 http://www.ijser.org